Gaute Solheim, Senior Tax Advisor, Norwegian Tax Administration

(Mr. Solheim writes in his individual capacity and does not purport to represent the views of the Norwegian Tax Administration.)

I happened to reread a paper by Wei Cui from 2017 on Third Party Information Reporting (TPIR) some weeks ago. Based on my own practical experience working for the Norwegian Tax Administration, I found it hard to agree with him on uselessness of TPIR. In this post, I will explain why I expect good quality in TPIR filing. I plan to write a later post on why TPIR is useful.

I will start with crediting Cui for outlining very well what I will call “the story of the corporate tax revenue collection machine.” He does a good job describing how the government has outsourced the bulk of the revenue collection to corporations. I would love to see papers adding empirical numbers to this description. My Norwegian perspective is a world of VAT, corporations withholding taxes on wages and delivering massive amounts of data used to prepopulate the personal tax filings. The way Cui describe the role of the corporations in the “tax revenue collection machine” is probably even more spot on for me than for a reader with a US perspective.

As I read Cui, he expect legal entities to cooperate sufficiently to ensure fairly good quality TPIR. He does some reasoning on why this is to be expected, but I did not find his arguments very convincing. This may be because for some years I have had a different line of reasoning ending with the same conclusion. What follows is based on material I used in a talk some ten years ago for my colleagues at the Large Taxpayer Office in Norway. The theme of that talk was why we found less evasion in our segment of taxpayers than what other tax auditors found when auditing smaller entities. I called the talk “The Human Factor in Tax Filing”. I believe the reasoning I used there also may explain high quality TPIR.

To make it clear: This is about tax evasion (or deliberately misreporting). Tax avoidance is a different beast.

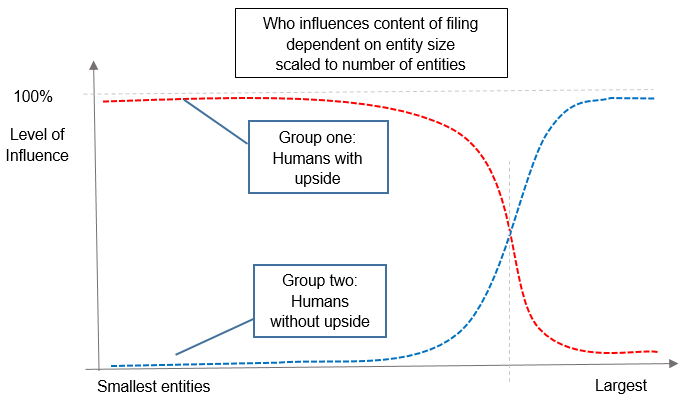

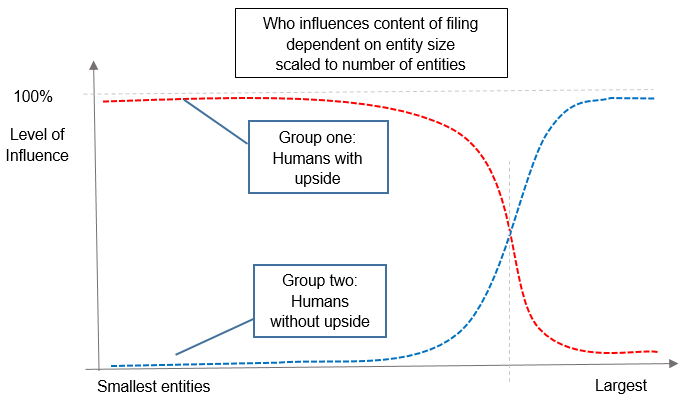

I started out by observing that legal entities cannot write, and hence are unable to fill out their own tax returns. They need human beings to help them. My next observation was that you can split these “helpers” into two groups. Group one is humans with direct economic upside from evasion, typically the owner(s) of the entities. Group two is humans with no direct economic upside from evasion, typically employees without an owner interest. My third observation was that the influence these two groups had on the filings was strongly linked to the size of the entities. In the smallest one-person owner/manager entities, people with direct personal economic upside from evasion (group one) have a large influence on the numbers filed. In the largest multinational corporations, people with no personal direct economic upside from cheating (group two) do most of the work.

Based on these unsystematic observations of reality, I made the following diagram of my estimate of how the influence of people with economic upside from misreporting (red line) and those without (blue line) varies as a function of entity size. The vertical axis goes from zero control to a hundred percent. On the horizontal axis, each entity is counted as one. I do not have empirical studies to back up any claim that the balance of influence between the two groups shift at a specific gross income or similar figure. If forced to make a guesstimate, I would, for Norway, say somewhere around USD 5 million, with big variations among business segments. I will, for the sake of simplicity, use USD 5 million as the crossing point.

I do not have empirical studies to back up any claim that the balance of influence between the two groups shift at a specific gross income or similar figure. If forced to make a guesstimate, I would, for Norway, say somewhere around USD 5 million, with big variations among business segments. I will, for the sake of simplicity, use USD 5 million as the crossing point.

I do not have empirical studies to back up any claim that the balance of influence between the two groups shift at a specific gross income or similar figure. If forced to make a guesstimate, I would, for Norway, say somewhere around USD 5 million, with big variations among business segments. I will, for the sake of simplicity, use USD 5 million as the crossing point.

I do not have empirical studies to back up any claim that the balance of influence between the two groups shift at a specific gross income or similar figure. If forced to make a guesstimate, I would, for Norway, say somewhere around USD 5 million, with big variations among business segments. I will, for the sake of simplicity, use USD 5 million as the crossing point.

Corporations with less than USD 5 million in revenue are by far the main bulk of the population. Based on this perspective, we would logically start wondering why all these entities represented by humans with incentives to cheat average to a compliance rate of 90% or better. This is the perspective I understand Cui is debating in the last half of his paper, and he formulated some explanations that did not fully convince me.

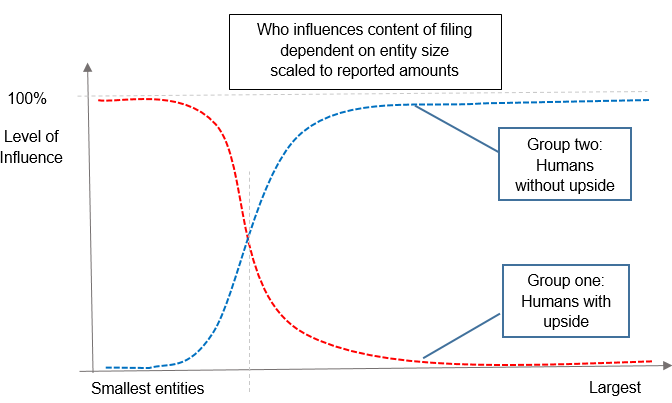

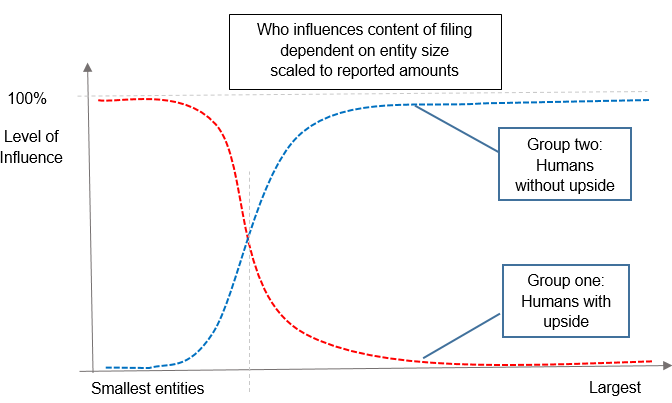

As a longtime tax auditor, the number of entities to me is an administrative problem. I’ve always measured my own work in money saved: How much of the tax gap did I manage to plug? To get this perspective on reality, I must change the unit of measurement on the horizontal axis from entities to dollars. Each entity claims a space equal to the share of the total government revenue collected or paid by that entity. Something very interesting happens to the perspective when we change from entities to dollars: The main bulk of government revenue is collected, reported and paid by the small group of big entities where the people with no upside is in full control over the numbers reported.

Something very interesting happens to the perspective when we change from entities to dollars: The main bulk of government revenue is collected, reported and paid by the small group of big entities where the people with no upside is in full control over the numbers reported.

Something very interesting happens to the perspective when we change from entities to dollars: The main bulk of government revenue is collected, reported and paid by the small group of big entities where the people with no upside is in full control over the numbers reported.

Something very interesting happens to the perspective when we change from entities to dollars: The main bulk of government revenue is collected, reported and paid by the small group of big entities where the people with no upside is in full control over the numbers reported.

I only have hard numbers for corporate income tax (CIT) in Norway to back up this perspective, but I am confident that it holds true in general. Sixty-five percent of all CIT in Norway is paid by entities with revenue higher than approximately USD 150 million. The corporations with billions in revenue and thousands of employees are few, but they represent the bulk of what matters. When we use this perspective—money—we see that individuals with no personal gain from non-compliance handle the main share of input to the revenue collection machine and TPIR. This is true whether the reports are on wages and taxes withheld from them, VAT, or the entities’ own corporate income tax.

There is another important human factor, the down side. I have observed legal entities with feelings only when someone employed by the entity has made a mistake and the mistake has become public. The public relation department will issue a statement telling the public “The entity is very sorry that a trusted person have failed to live up to the high ethical standards of the entity as explicitly laid out in internal memos, rules, etc.” Then they throw that someone under the bus. Everybody knows this.

Since everybody knows this, it would be strange if that knowledge did not shape the behavior of the people engaged in taking care of compliance tasks on behalf of the huge impersonal corporation. They have no personal gain and they know who the scapegoat will be.

Based on this rather simple analysis of the human factors involved, I am convinced that compliance and quality TPIR is what I in general should expect from large corporations. I do know from experience that in some particular settings this will not hold true, but the big picture is to expect compliance. I will now shift to the smaller entities.

Cui gives a few examples illustrating how the employer and the employee have a win-win scenario in misreporting (cheating). He leaves out some elements that I find very practical in real life. I must confess that a few times in my life it has happened that I was guilty of doing something qualifying at least for a fine. But I’ve never been tempted to do something that relied on recruiting a partner in crime. Somehow human nature realises without thinking too hard about it that conspiracy is on a different scale than a moment of weak ethics. If you do not figure it out on your own, the penal code makes that very clear.

The win-win situation described by Cui differs a lot from an owner/manager deciding to keep some income off the books. While you may do that alone as owner/manager, the Cui win-win may only be established by recruiting someone to take part in the scheme. In addition, the owner knows that employers and employees from time to time end up with conflicting interests. Lay-offs are but one example. From my limited knowledge of the US penal system and tax legislation, I have the impression that an employee deciding to inform the IRS about the misdeeds of a corporation may get much more lenient treatment than the corporation and the owner/manager of that corporation. As a hypothetical owner/manager, I would at least think twice.

This is not saying that this kind of collusion does not happen. It does, but the human factor and a simple risk analysis informs me that it should be more the exception than the rule. Undeclared income is a much more likely scenario in the small corporations than manipulated TPIR. This result is not produced by the integrity of the corporation, which I believe has none, but is what you expect from human beings when acting based on the incentives present in the situation. The sum of these very human choices is what we may call a compliant corporation, sending the tax authorities high-quality TPIR.

As Cui correctly observes, even high-quality TPIR is pointless if it does not contribute to something useful. Tax authorities are collectors of revenue, not of data points. Why I do not agree when Cui concludes that TPIR is not useful will be the theme for a later blog post.

And again: This was about evasion, not avoidance.